Patriarchal Society: Can Iraq’s women break political barriers in 2025?

Shafaq News/ As Iraq prepares for its parliamentary elections scheduled for November 11, 2025, the road to political participation remains fraught with challenges for Iraqi women. Despite a constitutional quota that guarantees women 25% of the seats in parliament, deep-seated societal norms, political exclusion, and legislative loopholes continue to undermine the potential for meaningful representation.

Legal Rights vs. Practical Realities

On paper, Iraqi women have equal legal footing with men in seeking parliamentary office. The Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) confirms that both genders must meet identical eligibility criteria: Iraqi nationality, full legal capacity, a minimum age of 30, and at least a bachelor’s degree. Additionally, candidates must have a clean legal record—free of corruption charges or final convictions related to financial misconduct or abuse of public funds.

“The law also prohibits candidacy for anyone still serving in military, security, or judicial positions,” IHEC spokesperson Jumana al-Ghalai told Shafaq News, reiterating the non-discriminatory framework outlined in electoral regulations.

However, experts and rights advocates say the practical experience of female candidates tells a different story—one marked by character defamation, digital harassment, and institutional bias.

Securing the 25% Quota

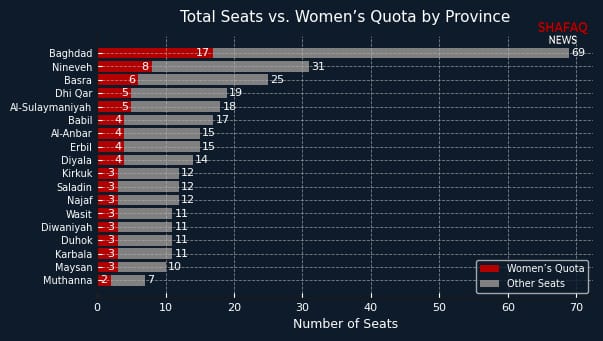

Under the amended Election Law No. 12 of 2018, women are guaranteed at least 83 of the 329 seats in Iraq’s Council of Representatives. These seats are distributed proportionally by province, based on population. Yet the implementation of this quota has done little to shield women from the cultural and political forces arrayed against them.

“Halabja will remain part of Al-Sulaymaniyah’s electoral district in the upcoming elections,” said Hassan Hadi Zayer, an IHEC media official. Granting Halabja its own seat requires a legislative amendment—one that has yet to materialize, further reflecting the sluggish pace of electoral reform.

IHEC member Saad al-Rawi also pointed out that the latest population census has not been factored into district allocations due to the lack of updated legal mechanisms.

Beyond the Ballot: Social and Political Obstacles

Many female candidates face persistent societal resistance once they enter the political arena. “Smear campaigns begin almost immediately after women announce their candidacy,” said Insam Salman, director of the Isen Organization for Human Rights in Iraq, in an interview with Shafaq News.

According to Salman, these attacks are often personal and disproportionately affect women who lack tribal protection or backing from influential political parties. “Iraqi society is still fundamentally patriarchal and views leadership roles as male domains. A woman’s political ambition is often seen as a challenge to male authority,” she explained.

This gendered hostility not only deters women from entering politics but also erodes their chances of sustaining meaningful political careers. While many women enter parliament under the quota, they are frequently sidelined from leadership roles within parliamentary committees or executive bodies.

Salman emphasized that addressing these challenges requires more than symbolic representation, “We need legislative deterrents to prevent defamation and to protect women in the public sphere. But more importantly, we need a cultural shift that normalizes female leadership.”

Structural Imbalance in Lawmaking

This exclusion of women has broader implications for governance. Political analyst Nawal al-Moussawi told Shafaq News that Iraq’s legislative process continues to suffer from gender and social imbalances, particularly in laws intended to protect women, children, and marginalized communities.

“There’s a deep-rooted distortion in how laws are crafted and who benefits from them,” she said. “Dominant political blocs often push legislation that reflects narrow ideological interests, sidelining issues that affect half the population.”

Al-Moussawi cited repeated attempts to amend the Personal Status Law—a key legal framework governing marriage, divorce, and inheritance—as examples of how conservative forces have attempted to roll back women's rights under the guise of legal reform.

Describing the current (fifth) parliamentary session as “a clear failure,” she warned that public confidence in democratic institutions is waning. “There is growing disillusionment among civil society actors and ordinary citizens. If nothing changes, we risk repeating this failure in the next term—or perhaps something worse.”

With elections drawing near, the conversation around women’s political participation has gained urgency. Yet for many advocates, the 25% quota is no longer seen as a sufficient benchmark. Experts stress that fostering inclusive governance requires both institutional reform and societal transformation.