The first word: Iraqis find hope in Sumerian symbols

Shafaq News

In a country where youth creativity increasingly thrives in the digital marketplace, a growing number of Iraqis are turning their gaze far back — to the dawn of civilization itself. Amid handmade crafts, digital art, and jewelry design, many are drawing inspiration from the symbols and stories of Sumer, the world’s first known civilization, which emerged more than 5,000 years ago in the fertile plains of southern Mesopotamia — the land that is today Iraq.

For these young Iraqis, the fascination extends beyond aesthetics. It reflects a concerted effort to reconnect with a heritage that laid humanity’s earliest foundations of urban life, law, and writing.

From Uruk and Ur to Eridu and Lagash, the influence of the Sumerian past still resonates across Iraq’s soil and memory. Now, those echoes are finding new expression — not in clay tablets, but in metal, leather, and digital design.

Future Wears History

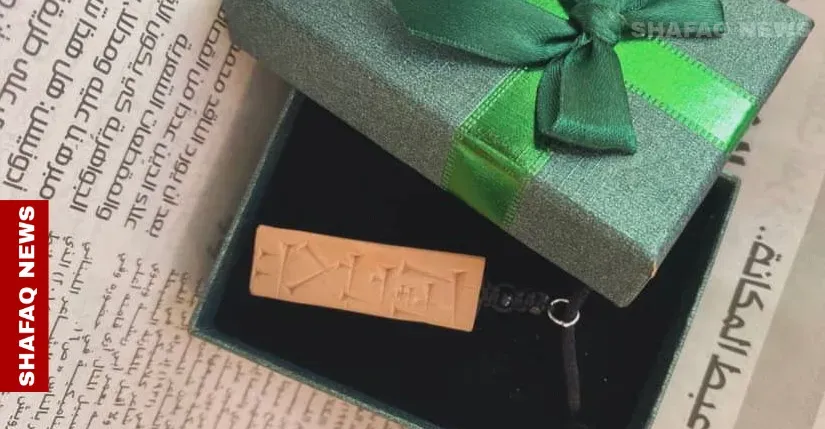

Among those spearheading this revival is Mustafa al-Rudaini, an artist and archaeologist from Baghdad who blends ancient language with contemporary craftsmanship. He converts cuneiform inscriptions — the wedge-shaped characters of Sumerian — into bracelets, pendants, and artworks that merge history with modern design.

“The idea came to me while studying archaeology,” Rudaini explained to Shafaq News. “I realized how disconnected many Iraqis have become from their own ancient identity. Through art, I wanted to rebuild that connection.” His designs are meticulously researched, each symbol reflecting historical and linguistic accuracy.

Al-Rudaini’s work offers a window into the rebirth of a language once thought lost forever. The Sumerian language, spoken by the inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia around 3100 BCE, was the world’s first written tongue — etched into wet clay with reed styluses.

Although it disappeared as a spoken language by 2000 BCE, scholars preserved it through Akkadian translations, and in the 19th century, it was deciphered from cuneiform tablets unearthed in Iraq. Today, Sumerian attracts archaeologists, philologists, and increasingly, Iraqis seeking a renewed link to their ancient roots.

Al-Rudaini’s revival aligns with this growing curiosity. Online, Iraqis share posts about learning Sumerian symbols, while universities report rising interest in Mesopotamian studies. “There’s a sense of cultural reawakening,” al-Rudaini observed. “We’re rediscovering who we are — not just as Iraqis, but as heirs of civilization itself.”

His handcrafted pieces, featuring inscriptions such as “freedom,” “love,” “life,” and “strength” in cuneiform, resonate deeply with Iraq’s youth.

“Every piece carries a message,” he noted, emphasizing that it’s not merely jewelry — it is identity in tangible form.

Heritage Sells

Al-Rudaini’s creations quickly attracted attention on social media, drawing buyers from Iraq and abroad. “Orders came from students, archaeologists, and even tourists,” he mentioned. “People want to feel connected to something that embodies pride — a history that began here.”

Beyond individual artistry, the revival reflects a broader cultural movement — an embrace of Iraq’s layered heritage beneath modern complexities. The Sumerian aesthetic has permeated décor, tattoo art, and fashion. “Sumerian symbols are not just historical artifacts,” al-Rudaini highlighted. “They have become a form of expression — a way of saying: We remember.”

Dr. Munahel al-Saleh, a sociologist at the University of Baghdad, interprets this fascination as both emotional and psychological. “After decades of conflict and fragmentation, Iraqis are reclaiming continuity,” she observed, noting that by reaching back to Sumerian roots, they find stability and meaning that transcend modern divisions.

She further emphasized that Sumerian imagery — once confined to museum walls — has become an accessible language of pride. “These cultural revivals are not nostalgia. They are acts of resilience. The youth are using art and language to signal: We existed long before destruction, and we will exist long after it,” she added.

Oldest Word Rings

This rediscovery extends beyond scholars and artists. Across Iraq, young people increasingly explore cuneiform symbols and integrate them into daily life.

Tiba Hassan, a university student from Najaf, wears a necklace engraved with the Sumerian sign for “hope.” “It reminds me that my ancestors once wrote this same word in clay thousands of years ago,” she reflected. “It’s a bridge between me and them.”

Similarly, Raad Mahmoud, a craftsman from al-Nasiriyah — near the site of ancient Ur — described how visitors to his shop frequently request Sumerian-themed souvenirs. “They view it as a mark of authenticity,” he remarked, emphasizing that it is distinctly Iraqi, not imported or imitated.

For Dalia Qasim, a graphic designer in Mosul, cuneiform patterns have become an integral part of her digital creations, from posters to logos. By weaving these ancient symbols into modern design, she creates a bridge between past and present, allowing Iraq’s earliest expressions of language to resonate within contemporary visuals.

These individual accounts point to a larger truth: the revival of Sumerian symbols mirrors the revival of memory. The world’s oldest written language — once buried beneath millennia of dust — now speaks again through the hands of Iraq’s new generation.

Read more: Siyyah: A timeless Sumerian dish that Iraqis still enjoy

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.